Introduction

The Soviet Union was known for its ambitious architectural projects, many of which symbolized the country’s strength and ideological aspirations. Among these was the grand vision of the Palace of the Soviets, an enormous skyscraper meant to represent Soviet power. However, despite the vast resources and effort invested, the project was ultimately abandoned. Today, it remains a fascinating what-if of architectural history. In this article, we explore the origins, design, challenges, and legacy of this unfinished masterpiece.

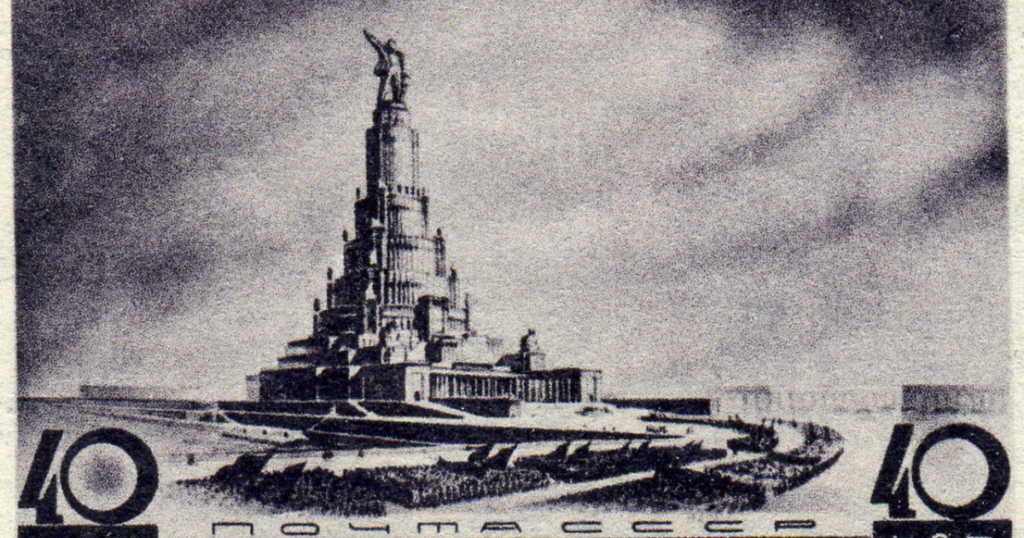

Origins and Grand Vision

The idea for the Palace of the Soviets was conceived in the early 1930s, during Joseph Stalin’s rule. Intended to be the tallest building in the world, it was to house government offices, meeting halls, and a massive statue of Lenin towering over Moscow. The palace would stand as a monument to Soviet superiority and communist ideology, replacing the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.

Architectural Design and Planning

The Soviet government held an international architectural competition, drawing entries from renowned architects worldwide. The winning design, chosen in 1933, was by Boris Iofan, featuring a neoclassical structure with strong Stalinist overtones. The palace was envisioned as a 415-meter tall skyscraper, topped with a 100-meter statue of Lenin. It would surpass the Empire State Building, symbolizing Soviet dominance in architecture and engineering.

The structure included grand meeting halls, libraries, administrative offices, and exhibition spaces. The design combined elements of socialist realism with technological advancements of the time, creating an architectural marvel that, if completed, would have redefined Moscow’s skyline.

Construction and Challenges

The construction of the Palace of the Soviets began in 1937. The foundations were laid, and initial steel frameworks were erected. However, several obstacles soon emerged:

- World War II (1941-1945): With the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, all resources and labor were redirected to the war effort. The construction site was abandoned as Moscow faced imminent threats.

- Post-War Economic Constraints: After the war, the Soviet Union struggled with economic devastation. Resources were prioritized for rebuilding cities and industries rather than ambitious architectural projects.

- Structural and Engineering Difficulties: The ambitious height and weight of the palace required advanced engineering techniques. The swampy terrain of Moscow made it difficult to create a stable foundation.

By the late 1940s, the project had lost momentum. Stalin’s death in 1953 further sealed its fate, as Soviet leadership shifted priorities. Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin’s successor, focused on practical and modernist urban planning, favoring mass housing over monumental structures.

What Became of the Site?

With the palace never completed, the abandoned construction site found a new purpose:

- During World War II, the steel framework was dismantled and repurposed for defense efforts.

- 1958-1960: The site was converted into an open-air swimming pool, known as Moskva Pool, the largest in the world at the time.

- 1990s: After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a controversial decision was made to rebuild the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour on the original site, undoing the Soviet-era demolition.

Legacy and Modern Reflections

Although the Palace of the Soviets was never built, its influence remains significant. It set the stage for later Stalinist skyscrapers, known as the Seven Sisters, which continue to define Moscow’s skyline today. The project also highlighted the Soviet Union’s grand ambitions and the challenges of merging ideology with practicality.

Architectural historians and urban planners still study the Palace of the Soviets as an example of unrealized potential and how politics shape infrastructure. Some architects even speculate about reviving the project with modern technology, though such plans remain purely theoretical.

Conclusion

The Palace of the Soviets remains one of history’s most fascinating abandoned projects. It was a vision of Soviet strength, yet its failure symbolized the limits of even the most ambitious authoritarian ambitions. While the structure never rose, its legacy endures in Soviet-era architecture, urban planning, and the ongoing dialogue about grand but impractical megaprojects. What if it had been completed? That remains one of the great mysteries of architectural history.